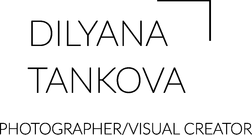

Forest Exposure

by Dilyana Tankova

Published by Flip Magazine 2026

When I first learned about shinrin-yoku, the Japanese practice of forest bathing, I thought it meant simply taking a mindful walk among trees. I didn’t realise I had been doing my own version of it all along, unaware of the exchange between our body’s chemistry and the forest’s, and how that hidden reciprocity keeps us both alive and healthy.

My connection to the forest is inevitable. Growing up in Bulgaria where nearly two-thirds of the land is covered in forest, it was always part of the stories we were told as children, the songs sang to us, the myths and the memories of our elders. It seems that those before us also understood the ancient power of the bond between humans and the forest.

There was a time when I suffered from severe migraines accompanied by aura which caused sharp flashes and would leave me powerless for hours, sometimes days; the migraine was a place I was dreading to enter voluntarily. I found ease through guided meditation and often my mind began to wander elsewhere. I would drift home to the forest near my grandparents’ village, as if my body had naturally and unforcedly found its own path of healing. I would drift down the narrow path between pines, surrounded by the smell of dry needles and mushrooms, the hum of birds and insects, the cool air circling a spring; every little detail, sound, scent and sensation, it felt as if my meditation lasted hours. Each time I returned there in thought, the pain would slowly step aside. I felt safe, as if the forest was holding me. After years of practising mindful shinrin-yoku meditations that I had invented for myself, my migraines stopped altogether.

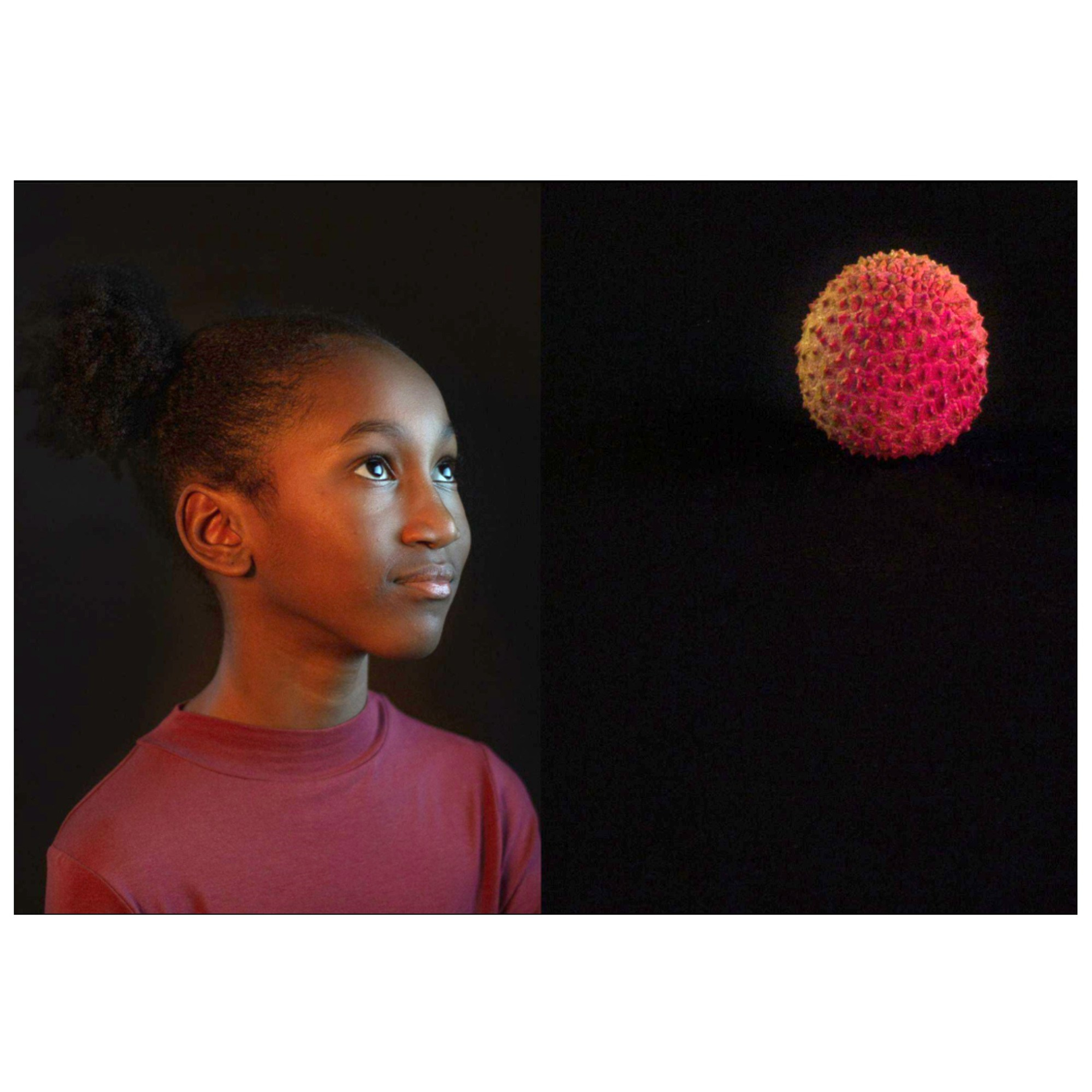

Not long after, I began studying photography and, unexpectedly, the same sense of calm returned, this time through the process of making images. The slow rhythm of creation mirrored the calmness of walking through the forest: preparing the image, the materials, working with light, waiting for something to appear. There was no rush, only presence. Both experiences required me to let go of control and trust a process larger than myself. That realisation drew me deeper into both worlds, the forest and the image making, until they began to merge. I started to explore whether image making could be another form of shinrin-yoku, an act of seeing and sensing that reconnects us to something else within ourselves.

In shinrin-yoku, the forest heals through the senses. The smell of soil, the shimmer of light, the texture of bark; each one reminds the body how to breathe again. It is less about escaping the world and more about remembering that we belong to it. The same happens when creativity seeps in slowly, through historical processes like salt printing or cyanotype. They depend on sunlight and time, on exposure and uncertainty. You cannot fully predict the outcome; you can only prepare, wait, and respond. These techniques are acts of attention, much like forest bathing. The light becomes your collaborator and natural elements leave their fingerprints on the final image.

Both art and the forest exist in a state of becoming. They respond, transform, and record time. When I create, I am not producing something separate from nature but participate in its ongoing rhythm. I began calling this connection Forest Exposure, a space where making and sensing intertwine.

It is not about photographing the forest. It is more about a state of being, both mental and physical, where belonging, creation, and timelessness coexist. It is a space of ease and acceptance; a meditation free from pressure, from hurry, from worry, from expectations, or fear of error.

Both the process of making an image and forest bathing, whether in person or through meditation, become a passage to elsewhere, an opening that invites slowness and awareness. In that space, time expands into different dimensions and the self dissolves into the wholeness.

These two worlds have always been my elsewhere, both real and imagined.